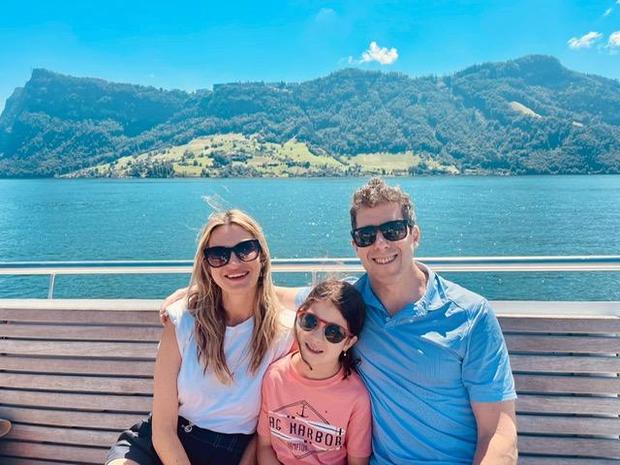

For decades, Phil Passen was an active runner and boxer. He jogged dozens of miles per week and regularly took park in competition, all while parenting his 9-year-old daughter and working in finance.

He felt fit and healthy — so when his primary care physician at New York University’s Langone Health told him he had a congenital heart condition that had never been detected before, he was shocked.

“I went for my yearly checkup … and my general physician caught that I had a heart murmur, and it sounded a bit abnormal,” Passen, 53, said. “She referred me for further testing, just as a precautionary thing. They didn’t find anything with a stress test, but then when they started doing the ultrasound, they discovered I had a bicuspid aortic valve.”

A bicuspid aortic valve means that a person has just two valves in their aorta, instead of the typical three. A bicuspid valve can calcify, narrowing the valve and making it harder for blood to flow correctly. The condition is typically corrected surgically, but when Passen’s was first detected in 2016, it wasn’t yet at that stage. Instead, he and his family entered a “wait-and-see” period: Every year, Passen would have regular cardiology checkups to monitor the situation.

“I kind of had to put my mind in the frame of ‘OK, this is something that needs to be monitored, and I can’t mess around with it,” Passen said. “So if it does get serious, I’m just going to have to not ignore the symptoms and just do what needs to be done.”

In 2020, two things happened: The coronavirus pandemic struck the United States, and the Passen family moved to Miami, Florida. Passen had yet to find a cardiologist in his new city, and he avoided doctors offices’ during the early stages of the pandemic. He wasn’t alone: 41% of people reported missing appointments in the early months of the pandemic, according to the American Medical Association.

For three years, Passen missed his regular check-up. He told CBS News that he was still running 25 to 30 miles a week, and he didn’t have any alarming symptoms like shortness of breath, chest pain or lightheadedness. In April 2023, he finally made an appointment with a doctor in Florida, only to hear the news he’d been dreading.

“They said to me ‘You need immediate surgery on your heart valve.’ This was the last thing I was expecting,” Passen said. “This is like a life-altering moment, because it’s suddenly not an elective surgery, and you’re being told that you need this done, and you need it done right away. It was probably the most stressful moment of my life.”

Finding a second opinion and a new option

Passen decided to seek out a second opinion from his former cardiology team. After an initial appointment, where he was told surgery would be necessary in the coming months, he had a follow-up appointment to discuss options with cardiothoracic surgeon Dr. Mark Peterson, the director of aortic surgery at NYU Langone.

The two most common surgeries each had downsides. Passen could get a replacement aortic valve from an animal source, but those valves tend to need replacing after about ten years, leading to more surgeries down the line. Another option was a prosthetic valve made from pyrolytic carbon, but Passen would then have to take blood thinners for the rest of his life and be unable to play contact sports. The prosthetic option also negatively impacts life expectancy, Peterson said.

So Peterson presented Passen with a third option: A complex surgery called a Ross procedure. During this surgery, the aortic valve is replaced with the patient’s own pulmonary valve, and the pulmonary valve is replaced with a donor valve, Peterson said.

“The Ross procedure is obviously a little more complicated than a standard tissue or mechanical valve replacement, but … that short-term, more involved operation pays dividends over the long term,” said Peterson. “It restores survival to the normal life expectancy, you don’t have to take a blood thinner, and patients generally enjoy excellent quality of life.”

It was a riskier option. But it would give Passen the life he wanted.

“I just decided it was worth doing the more complicated surgery and lowering the risk of having to have another operation, even in 10 years,” Passen said. “I just decided that I don’t want to relive the fear of needing a new heart valve when I can do a surgery that’s going to dramatically reduce the chance of that happening.”

Once the decision was made, Passen said he began training for the surgery like he had for athletic events. From December to March, he made sure to keep up his exercise regimen, hoping being in shape would lead to a faster recovery later. Finally, it was the day of the operation.

The Ross procedure takes about four hours, Peterson said. Passen’s operation went smoothly, Peterson said, and within two hours of waking up from the operation, he was walking laps in the intensive care unit. Two and a half days later, he was discharged.

Now, nearly six months after the operation, Passen is back to running regularly and even took a family vacation to France over the summer. He credits the Ross procedure for his rapid recovery and for letting him return to the workout activities he loves.

Passen said he hopes his story inspires others to monitor their health.

“Once you’re above 40, you should be not only getting a yearly physical checkup, but you should have your heart checked as well,” Peterson said. “Many times there’s probelms that you don’t even know about, and the sooner it can be detected, the better it can be handled.”